Greetings, bonjour, what’s happening?

I thought I’d write a thing, being that on Thursday (24th) I’m doing an event which is celebrating 10 years of Beats & Elements at Camden People’s Theatre, in London. B&E is the theatre company I co-set up back, with my good pal Conrad Murray. We’ve made shows that tend to look at issues of social-class in Britain and use rap, beatbox, live-looping and spoken word to tell those stories.

Hopefully, by writing this, it will highlight the importance of genuine investment in theatre makers and artists, the type of which we were fortunate enough to get. When I say investment, I’m talking about space, time and opportunities to try things out in front of audiences. Getting programmed into theatres, and yes, money. Dough. Spondoolies. Reddies. Paper. But the bits before money are, I’d say, a lot more important, especially in the early stages of trying to create something.

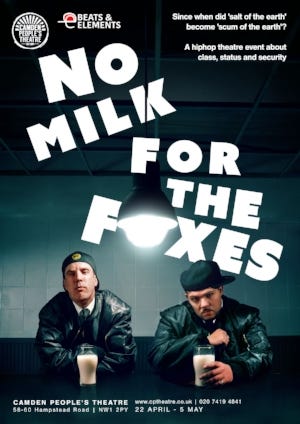

Despite the 10 year event tagline, we actually started Beats & Elements back in 2013. Our first show, was in 2015 and that was No Milk for the Foxes. The timelines aren’t quite exact but by the time that show first went up, we’d already a done a number of performances and events at Camden People’s Theatre (as well as Battersea Arts Centre and the Brockley Jack) as part of the show’s development; including performing at their 20th and 25th anniversaries (Our 10-year bash coincides with their 30th anniversary and also my 5th wedding anniversary; a triple celebration, no less)

CPT supported us from the off. They gave us that much needed space and time to develop that show (and subsequent shows and projects.) And crucially, they didn’t ask too many questions about what we were trying to make. They trusted us to get on with it. As that first show progressed, they then supported us to get funding for it and run workshop programs in their local community, which is something we wanted to do.

When you’re trying to make theatre, especially in a city like London, space and time is what you need (as well as money, but that comes much later) From what I can tell, this kind of support is very difficult to get now. It was difficult back then; hence we were fortunate but now? I don’t know what younger theatre companies do. Venues and organisations seem much more risk averse, especially with something that might seem a bit controversial or go against the grain of perceived wisdom. We had things we wanted to say and ways of saying them, that probably wouldn’t get passed the sensitivity complex these days. Like I said, they just let us get on with it, even if they may not have always agreed with what we were saying; they let us breathe and find our feet.

When we first set out, me and Con sat down at Foyles on Charing Cross Road. We wrote down what we wanted to do. Run workshops in schools and local communities and make shows based on the kind of people we both knew. The kinds of people that we weren’t seeing on stage, or screen. But this had to be done using our own vernacular, our own lexicon. Language. Clothes. Caps. Rap. Beats. Banter. We wanted to show the characters as three dimensional. Light and shade. Good, bad, and everything in between; how it should be.

Too many times we’d seen things which portrayed working class people as either evil or saintly. Nothing in between. Also, despite London having a rich history of theatre, with more theatres than it knows what to do with, it seemed rare to see shows that featured working class Londoners in it, or even lower middle-class Londoners; let alone shows written and created by them. This problem persists. In some ways it has improved, just so long as you’re singing from the same hymn-sheet as the gatekeepers and funders; then you might get a shot.

There’d been similar-ish shows before us, of course. But too me, the ones I saw, were either from, or for, a very middle-class perspective and audience. I’d say that’s still true now, maybe more so. Whether it’s crowbarring in some message about the environment or referencing whatever social-justice issue is relevant at that time, or just middle-class people writing shows about the working classes; but done badly. (For the record, neither of us have an issue with people writing about people from different backgrounds, we just like to see it done well.)

Though Conrad and I are from different backgrounds - him being from South London and growing up on council estates - and me – being from Horley, in Surrey, in a lower middle-class family - we felt we had a lot in common and shared similar views on many things. We also both rapped and had a background in music. We’d both had to experience the difficulties and pressures of just trying to keep your head above the water, whilst doing mind-numbing, low-paying jobs; having seen our parents do similar things.

I’ve never shied away from my background. Sometimes I’ve noticed people cock their eyebrows a bit, when I talk about where I grew up and the environment around me, especially with the types of noises that Foxes was making - as if I’m not supposed to be saying what I’m saying. I’m fully aware of what I had, and what I didn’t have, growing up. I had two loving and supportive parents in a fairly leafy area. However, the smaller material realities were somewhat different to how they’re sometimes perceived. The situation that the characters Mark and Sparx find them themselves in - skint and trying to pay bills – has been a constant for me my whole life.

Con was probably the first person I met who read a lot of books, bar my own parents. I didn’t know many people that read books and was quite embarrassed about my own little reading habit. I kept it hidden. My parents always encouraged me and my siblings to read books and question things. Those traits probably set me apart from some of my more working-class friends. Truth is, I never felt like I was either working class nor middle class. Hence, I use the term lower-middle. Not that it should matter all that much, but when you’re in a consciously, or even unconsciously, class-obsessed society like England; I guess it does.

The issue of class was always something that interested me; as it did with Conrad. We’d talk a lot, lend each other books and share articles to read. Owen Jone’s first Chavs book was one we both read. Class was an issue that seemed to have been brushed under the carpet. If it wasn’t David Cameron pronouncing that ‘we’re all middle class, now’ then the issue itself, was probably buried under the rising tide of identity politics and the various social justice theories that became prevalent in the arts. These mainly focused on race, sex and gender. Class barley got a mention, perhaps it was too difficult to define, as all the SJ stuff always had a very clear target for who to blame. But little of this reflected what we were seeing and experiencing around us. Class affects everyone. Maybe that’s the problem.

London had become ridiculously expensive to live in. Scores of young people had gone to university, got themselves into huge amounts of debt, on the promise of lucrative, highly-skilled careers, that for the most part, didn’t seem to exist, or if they did, they were going to the usual suspects who went to the right schools and uni’s etc. The jobs available to them, relative to the cost of living, were poorly paid. Meanwhile those at the lower end of the jobs market had to contend with zero hours contracts, doing jobs that at one time, would’ve offered security and enough money to live on. To date, while those living costs have continued to rise, the wages haven’t.

The opportunities to move into careers like ours, in the arts, became less and less for people from working class backgrounds or even lower-middle class backgrounds, like mine. The pool of people the arts and media worlds seemed to be drawing from, became increasingly narrow - therefore the type of work being created, more homogenised. Too similar. Too safe. Didn’t feel it. It was frustrating to see.

All of the above was the background to us starting to make some stuff together. So while both working at Battersea Arts Centre, we by chance bumped into Brian Logan one night, who directed the first show I was ever in at BAC, when I was doing youth theatre, there. He asked what we were up to. We told him about the little piece we were working on. He then told us he’d just taken over as artistic director at Camden People’s Theatre and invited us up there for a chat. We went up to Euston, sat down with Brian and told him about the company we were trying to get going. We also showed him a video, of a 15 minute exert of this piece, we’d performed at one of Battersea Arts Centres’ legendary Scratch nights (which they sadly no longer do.) He seemed really interested and quite quickly, gave us some of that crucial space and time to develop it, as well as the chance to perform a short 15 minute section, at an event he was programming.

We repeated this process a few times. Each time, showing another section that we’d made, in front of an audience, until we had a solid hours’ worth of raw material. We performed that one hour, it went really well and afterwards, CPT sat us down and offered us a full three-week-run the following year, with development time, as well as the support to get the funding to finish it and put it on. This would pay for a producer, two dramaturgs, lighting, set designer, marketing, props and costume. They also sourced funding for us to run a bunch of workshops at local community centres, all of which led to CPT setting up a youth theatre, which still exists to this day. At the time, out of necessity, both Conrad and I had gone back to having day jobs in schools, so we had to do all of this on top of doing our day jobs. But we did it and it was worth it.

We were the lucky recipients of two of those infamous phrases – right place right time and it’s not what you know, it’s who you know. As lucky as we were, we’d grafted to put our first ideas together. For that original scratch at BAC, we’d applied under the name of Beats & Elements, not our own names. We were both known in that building, especially Con, who’s done stuff there for years. We had relationships with the producers. But we wanted the work to stand on its own, they didn’t know it was us. By the time the show the show first went up, in 2015, it’d been over 2 years of making it before we’d seen any dough; bar a couple of small performance fees CPT gave us for those early events. We just made the thing and hoped, that if it was any good, then the money would come. And if it didn’t, we would just do it anyway.

For a small venue, CPT went above and beyond with they did for that show. Alongside the PR people, they secured us a whole bunch of reviews and coverage that I don’t think we would’ve got anywhere else. We did interviews with The Guardian and The Camden Journal and got featured on a podcast. All the ingredients were there for us to go in and do our job. The perfect set up for a goal, we had just to stick the ball in the net.

The show was successful and we seemed to generate a genuine buzz. By the last week of the run, we had no idea who was coming in. When you’re at this level, you’re mostly relying on friends and family to buy tickets, but we went beyond that. We bought a lot of people into that theatre for the first time, people that wouldn’t normally watch theatre, as well as attracting groups of academics, students and journalists. CPT let us programme our own post show performances, where we had beatbox-battles, rap freestyles, spoken word artists and performers, all sharing the stage with us.

The one thing we never got to do with Foxes, was tour it. CPT were already at capacity just managing us and all the many other shows and artists they programme. Our producer, Lara Taylor, got a full time producer job and neither me or Con had the knowledge or wherewithal (in my case) to try and make it happen. So that’s where the show stayed. Thank God we had the filmed version (though getting that back and uploaded, took over five years and is another story altogether)

Not long after the Foxes show, Con got me to read JG Ballard’s High Rise. We got talking again. Got to throwing ideas around, which lead to the next show High Rise eState of Mind. We both wanted to bring in some other collaborators for this one. David Bonnick Jnr (Gambit Ace) and Lakeisha Lynch-Stevens had performed at our Foxes post-show events and smashed it. They had ideas and skills. Gambit and Conrad go back years, in both theatre and music, with TDC and Rodium. We’d met Lakesiha doing stuff at BAC. They got what we were trying to do.

We got to working and repeated that making process all over again. Grinding out material, doing little scratches here and there. CPT came on board as a producer, alongside BAC and GL4 Gloucester, with Sarah Blowers as producer. We assembled a great team, bringing back Simeon Miller as lighting designer from the Foxes show, who made this nuts Kayne-esque lighting design, all courtesy of another funding grant from the Arts Council.

Like Foxes, the money didn’t come till much later in the process. There was two or three years of no dough; just grafting. But what we did get, was that crucial space and time, again. A room here and a room there, a speaker here and a PA there; so we could jam, talk and make stuff; with a couple of scratch performances along the way to build up the momentum.

High Rise went up in 2018 and again, we had a really good reception with some great coverage. We went on London Live TV and BBC London promoting the show, as well as countless reviews. This time around we were able to do a small tour, which included runs at Battersea Arts Centre, Camden People’s Theatre, then nights in GL4 Matson, Gloucester, Home Slough, Fairfield Halls Croydon, Home Manchester and then the Southbank Centre, London. In-between all of that, COVID happen, which turned the industry on his it’s head. Things haven’t quite been the same since, but I’m glad we did get those shows in.

In hindsight, both of those shows could’ve had a longer life. People still ask us about them, now. Getting to perform parts of them again, at CPT, will hopefully breathe new life into them, or at least remind people about what we created. Those problems I mentioned at the start, in terms of trying to make shows, are still as prominent as ever. I sometimes wonder, if we were starting out now, would we get anything off the ground? It’s tough times, indeed. But, if you’re able to get the investment, the way we did, then some good things can be created with a legacy. In answer to my own question, we probably would have made something, but nowhere near to the level of what we did. We never relied on funding, but it certainly helps when you get it…

In 2022, those shows, plus Conrad’s Demarked, were published by Methuen Drama, in Beats And Elements: A Hip Hop Theatre Trilogy and live on in the scripts. We know of at least one uni who apparently now has us on their reading lists and we’ve been cited in a few essays, which is nuts to me. We started this in Conrad’s studio, just two geezers jamming some ideas around and we got lucky enough to have an organisation, like CPT, come and invest some time, space and eventually money in us. And we created something. Which lives on.

Large up the risk-takers. Large up the space-givers. Large up the dough-providers. Large up Battersea Arts Centre, GL4, Strike A Light, Polka Theatre and everyone else that’s supported us along the way. Especially large-up Camden People’s Theatre, thanks for everything and happy birthday. Happy birthday us.

LINKS

NO MILK FOR THE FOXES FULL SHOW - filmed at Camden People’s Theatre 2015

NO MILK FOR THE FOXES MUSIC VIDEO

HIGH RISE ESTATE OF MIND TRAILIER